The Deacon, Deacon’s Digest, FREE resource bulletin

The Deacon, Deacon’s Digest, FREE resource bulletin

February 15, 2026

February 15, 2026

6th Sunday of Year A

An Unforgiven Homily Connection

Why would a preacher’s preparation website go rogue? We’re doing a deep dive into The Word This Week, a resource for Catholic homilies that usually showcases standard anecdotes and illustrations for its homilies. But for the Sixth Sunday of Year A, the website threw out the rulebook. On today’s DEEP DIVE podcast we explore an audacious FAITH & FILM entry that links the biblical book of Sirach to the brutal world of Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. Join us as we dissect this unlikely pairing and ask the big question: How can a story of violent men and “the angel of death” unlock a profound—and terrifying—truth about human freedom? It’s theology like you’ve never heard it before.

The Burden of the Outstretched Hand: Volition and Violence in Unforgiven (1992)

When looking for movies that resonate with the scripture readings for this week, THE WORD THIS WEEK wasn’t necessarily looking for “religious” movies. It was looking for films that explore the burden of choice, films that reject determinism (the idea that our actions are predetermined by past events or biology), and films that show characters facing a definitive moral crossroads where the outcome is entirely up to them. We think we found it in Unforgiven (1992).

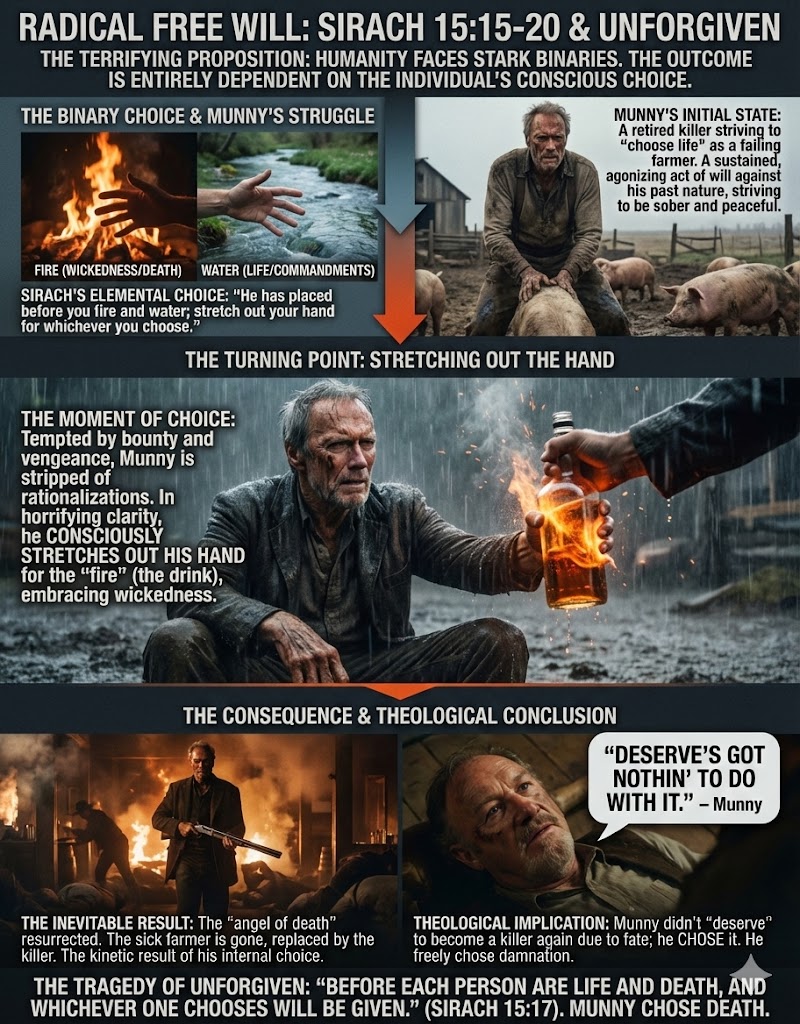

The core themes of Sirach 15:15-20 are:

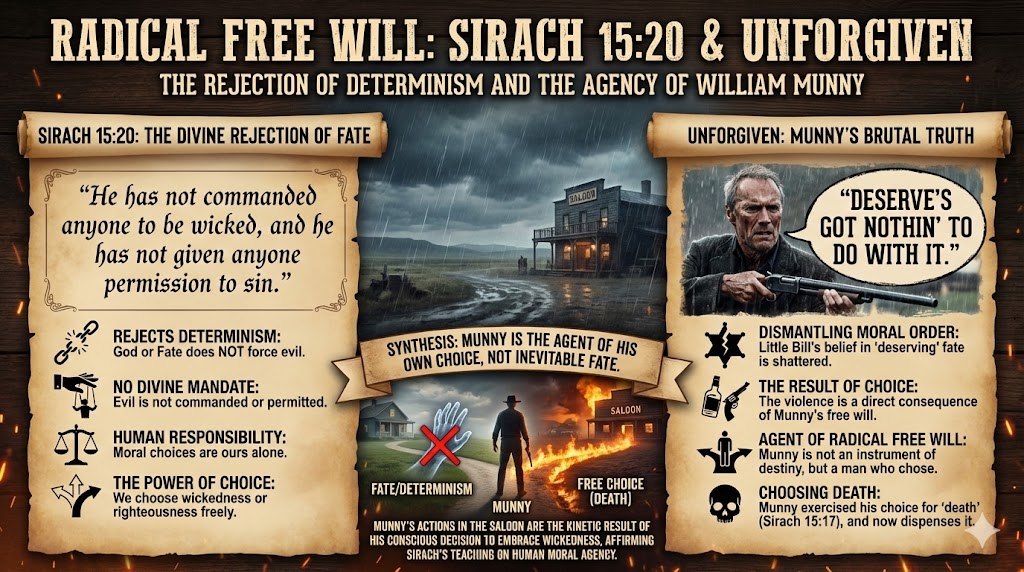

- Radical Free Will: Humans possess absolute moral agency. We are not puppets of fate, environment, or even God’s foreknowledge.

- The Binary Choice: The moral universe is presented as a stark choice between opposites: commandments vs. wickedness, fire vs. water, life vs. death.

- Personal Responsibility: Because we are free to choose, we are fully responsible for the outcomes of those choices. God does not cause us to sin; we choose to stretch out our hands toward evil.

MOVIE RECAPS & EXPLANATIONS (12:39): Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) is a dark, haunting masterpiece that redefines the Western genre. This deep-dive explores William Munny’s journey from repentant farmer to ruthless killer, revealing how violence, guilt, and redemption intertwine in a world without heroes. Through a full story recap and deep analysis, we explore how Unforgiven exposes the myth of the gunslinger, questions the morality of justice, and confronts the price of vengeance. From Gene Hackman’s terrifying Little Bill to Morgan Freeman’s tragic Ned, every character reflects a different shade of humanity — flawed, broken, and unforgettable. If you think you know what a Western is, think again. This is Unforgiven — brutal, poetic, and uncompromising.

To Pick Up the Fire: The Terrifying Theology of Clint Eastwood

The wisdom of Sirach 15:15-20 presents a terrifying theological proposition: the “fire” of wickedness is not a destiny we fall into, but a choice we must actively make. The text dismantles the comforting defenses of determinism, fate, or divine pre-ordination, placing humanity before stark binaries—fire and water, life and death—and insisting that the outcome is entirely dependent on what the individual chooses to grasp. Clint Eastwood’s masterpiece Unforgiven serves as a brutal, cinematic exegesis of this specific theology. It is a film about a man who desperately wants to believe his choices were decided for him by a violent nature, only to confront the horrifying reality that he is terrified of the fire precisely because he knows he is free to pick it up again.

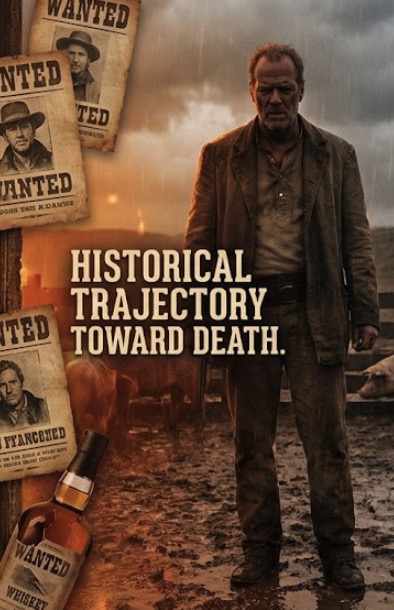

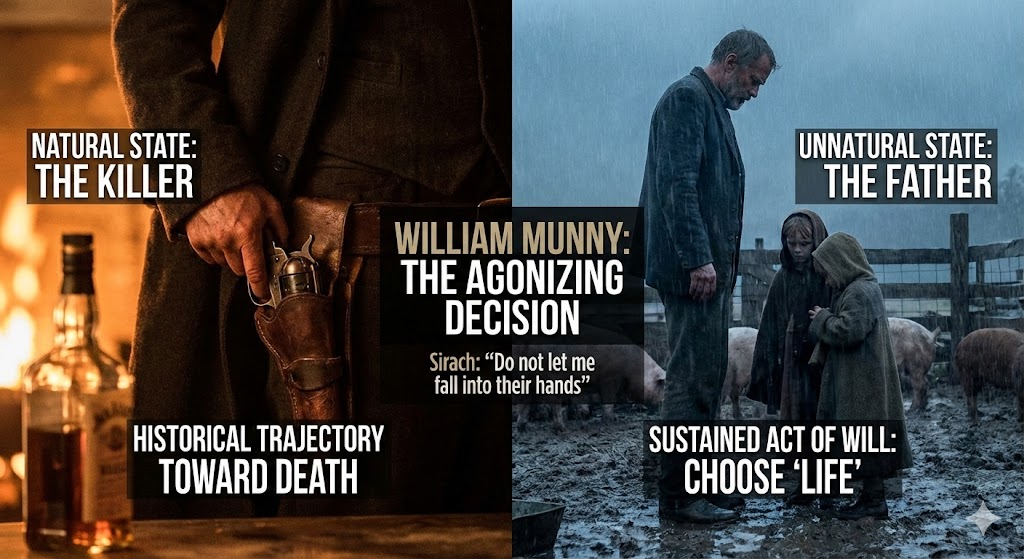

William Munny is introduced as a man engaged in a violent struggle to choose “water.” We find him not amidst the flames of his past, but knee-deep in the mud of a failing pig farm—a messy, difficult immersion in the life he is trying to sustain. A “man of notoriously vicious and intemperate disposition,” he is now sober, mourning the saintly wife, Claudia, who “cured” him. In the language of Sirach, Munny is striving to “keep the commandments” and “act faithfully” despite the difficulty. This existence is agonizing for him; it goes against his grain. Yet, it represents a sustained, conscious act of will to choose “life,” effectively dousing his own historical trajectory toward death.oward death.

The tension of the narrative arrives not through inevitable fate, but through the mechanics of temptation. When the Schofield Kid rides in to offer a bounty on two cowboys who cut up a prostitute, he places Munny directly before Sirach’s elemental choice: “He has placed before you fire and water; stretch out your hand for whichever you choose.” The Kid brings the spark, but the choice remains Munny’s alone. The film presents this not as a heroic call to adventure, but as a seductive invitation to abandon the difficult “water” of the farm for the familiar, burning clarity of his old life.

The brilliance of the film lies in the slow, agonizing creep toward the fire. Munny does not leap into the inferno; he inches toward it, constructing rationalizations to shield himself from the heat of his own decision. He tells himself, and his reluctant partner Ned Logan, that they aren’t “like that no more,” insisting this is merely a job for justice rather than a return to sin. Yet, as they ride toward Big Whiskey, Munny’s physical degradation—his fever, his inability to shoot straight, and the brutal beating he endures from Sheriff Little Bill—serves as a visceral manifestation of a soul in conflict. His body seems to violently reject the transition, physically breaking down as he attempts the impossible: holding onto the “water” while walking straight into the flames.

The defining moment of the film, and its strongest resonance with Sirach, occurs just before the climax. Munny is recovering outside of town when word arrives that Ned has been whipped to death by Little Bill and displayed in a coffin outside the saloon. Munny sits in the pouring rain—the ultimate manifestation of the “water” he has tried to live within—finally stripped of his rationalizations.

It is here that the moral agency described in Sirach becomes tangible. Throughout the film, Munny has refused whiskey, recognizing it as the accelerant for his dormant nature. Now, sitting in the mud, a bottle is offered to him. The camera lingers. No one forces the glass to his lips. Fate does not pour it down his throat. In a moment of horrifying clarity, Munny “stretches out his hand” and grasps the fire.

That single motion is the embrace of wickedness that Sirach 15:20 warns God does not command. By taking the drink, he consciously sheds the reform of William Munny the pig farmer and chooses to resurrect the angel of death. The subsequent massacre at Greeley’s saloon is merely the inevitable kinetic result of that internal choice. When he walks into the saloon, the clumsy, sick man is gone, replaced by a terrifyingly efficient killer.

When Little Bill, lying dying on the floor, protests, “I don’t deserve this… I was building a house,” Munny delivers the film’s thesis: “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.” While Munny means that death comes to all regardless of merit, through the lens of Sirach, the line takes on a darker theological weight. Munny did not become a killer again because of fate or what he “deserved,” but because of what he chose. Sirach 15:17 concludes, “Before each person are life and death, and whichever one chooses will be given.” William Munny stretched out his hand for death. The tragedy of Unforgiven is not that redemption was impossible, but that when faced with the ultimate binary, Munny simply put down the water and picked up the fire.

Discussion Questions

The Elemental Binaries

Question: Sirach 15:16-17 states: “He has placed before you fire and water; stretch out your hand for whichever you choose. Before each person are life and death, and whichever one chooses will be given.” How does the film Unforgiven visually or thematically represent these elemental binary choices in the life of William Munny?

Answer: The film represents these binaries through Munny’s two distinct existences. “Water” and “Life” are represented by his current life as a pig farmer: it is muddy, difficult, and humiliating, but it is sober, non-violent, and rooted in the redeeming love of his deceased wife, Claudia. “Fire” and “Death” are represented by his past reputation, the bounty money, the gun, and, most potently, whiskey.

The entire film is Munny standing between these two options. He desperately wants to choose the “water” of his quiet farm life, but economic desperation and pride tempt him toward the “fire.” The tragedy of the film is that the binary is real; he cannot have both the bounty money and his redeemed soul.

Physical Resistance as Spiritual Struggle

Question: Throughout the middle section of the film, as Munny rides toward the confrontation in Big Whiskey, he is physically degraded. He suffers from a severe fever, he cannot shoot straight, and he is easily beaten by Little Bill. Viewing this through the lens of Sirach’s emphasis on individual moral agency, how might we interpret Munny’s physical weakness?

Answer: If we accept Sirach’s premise that Munny is fundamentally free to choose goodness (“If you choose, you can keep the commandments”), his physical sickness can be viewed as a manifestation of his soul’s resistance to the bad choice he is currently making.

His body is rejecting the return to his old self. He is trying to hold onto the “water” (his reformed nature) while actively riding toward the “fire.” The fever breaks only after he has been beaten and humiliated—perhaps symbolizing the breaking point of his resistance, preparing him for the final, terrible choice that follows.

The “Outstretched Hand”

Question: Sirach insists on the physical act of volition: “stretch out your hand for whichever you choose.” Analyze the pivotal scene where Munny sits alone in the rain after learning of Ned’s death and is offered the whiskey bottle. Why is this specific action the most critical moment in the film regarding the Sirach connection?

Answer: This is the definitive moment where the theological concept of Sirach becomes cinematic action. Throughout the film, Munny has refused whiskey, knowing it is the fuel for his internal “fire.” Whiskey is the gateway to his past self.

Sitting in the mud, stripped of the rationalizations that this was just a “job for justice,” he faces the raw reality of Ned’s death. When the Schofield Kid offers the bottle, no one forces it to Munny’s lips. Fate does not pour it down his throat. The camera lingers on the agonizing pause before Munny physically “stretches out his hand” and grasps the bottle. In that split second, he actively chooses to let William Munny the farmer die, and to resurrect the notorious killer. It is a conscious embrace of wickedness.

Rejection of Fate and “Deserving”

Question: Sirach 15:20 states, “He has not commanded anyone to be wicked, and he has not given anyone permission to sin.” This verse rejects the idea that God or fate forces anyone to be evil. How does Munny’s famous final line to Little Bill—”Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it”—resonate with this rejection of determinism?

Answer: Little Bill dies believing in a moral order where civilized men who build houses shouldn’t be shot down in saloons. He believes he doesn’t “deserve” this fate. Munny’s reply brutally dismantles that notion.

Through the lens of Sirach, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it” means that what is happening in that saloon is not the result of cosmic karma or inevitable fate. It is happening because Munny chose to pick up the bottle and the gun. Munny isn’t an agent of unavoidable destiny; he is a man who exercised his radical free will to choose “death” (as per Sirach 15:17). Because he chose death, death is what he is now dispensing.

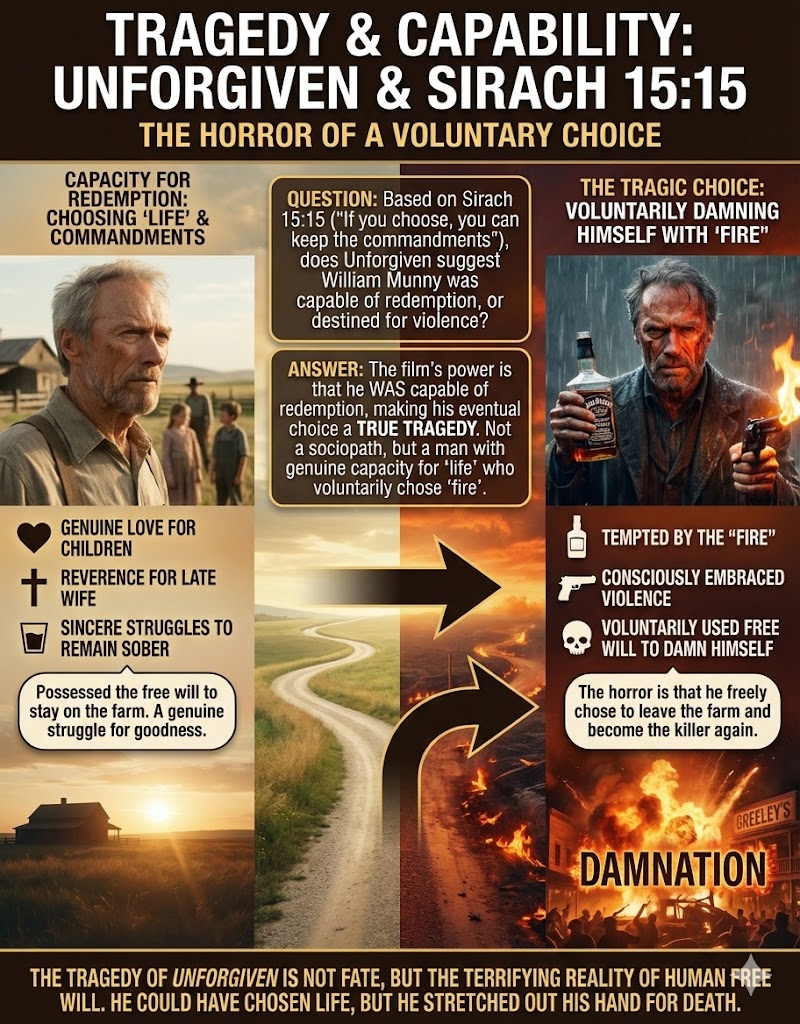

Tragedy and Capability

Question: Based on the reading of Sirach 15:15 (“If you choose, you can keep the commandments”), does Unforgiven suggest that William Munny was capable of redemption, or was he always destined to revert to violence?

Answer: The power of the film lies in the fact that he was capable of redemption, which makes his eventual choice a true tragedy. If Munny were simply a sociopath incapable of change, the film would be a grim action movie, but not a tragedy.

We see his genuine love for his children, his reverence for his late wife, and his sincere struggles to remain sober. He has the capacity to choose “life.” The horror of the ending, viewed through Sirach, is that he possessed the free will to stay on the farm, but when tempted by the “fire,” he voluntarily used that same free will to damn himself.

This section of THE WORD THIS WEEK website cultivates discernment and wonder by analyzing how the stories we watch interact with the Greatest Story ever told. Whether it’s a superhero grappling with sacrifice, a horror film exploring the reality of evil, or a drama depicting the beauty of forgiveness, we believe every frame offers a chance to engage with the Gospel. Movies are more than just entertainment; they are modern parables that reflect the deepest longings of the human heart—our desire for redemption, our struggle with sin, and our search for truth. We aren’t just looking for “safe” content or counting curse words; we are looking for God’s truth in unexpected places.