September 7, 2025

September 7, 2025

Sacraments

Sacraments Baptism Eucharist Confirmation Confession Anointing of the Sick Marriage Holy Orders

Living the Word through Sacramental Grace

FATHER MANUEL (3:47) – This song is a tribute and prayer to the millennial saint Carlo Acutis. Carlo Acutis was beatified on the 13th of June 2020 by Pope Francis and the canonization would be done by Pope LeoXIV. Carlo Acutis has become an inspiration for the GenZ with his love to the Eucharist, and he so beautifully calls it the Highway to heaven. Carlo Acutis pray for us.

- BAPTISM

- EUCHARIST

- CONFIRMATION

- CONFESSION

- ANOINTING OF SICK

- MATRIMONY

- HOLY ORDERS

- DEEP DIVE

BAPTISM

A Path Made Straight

The reading this Sunday poses a question that contains its own beautiful answer: “who ever knew your counsel, except you had given wisdom and sent your holy spirit from on high?” (v. 17). This reveals the core of our hope. Left to ourselves, our deliberations are timid and our paths unsure.

The Sacrament of Baptism is the very moment God answers this question for each of us, sending His “holy spirit from on high” to dwell within us.

The unique daily grace of Baptism is this constant access to our divine counselor. It is the grace that reorients our lives, allowing us to begin learning what is pleasing to God. In our daily vocations, relationships, and moral choices, we are no longer left alone. By prayerfully turning to the Spirit given at our baptism, we receive the wisdom needed to walk with confidence, trusting that our “paths…on earth [are] made straight” (v. 18b).

First Reading

23rd Sunday of Year C

Reflection Questions

- Our mortal deliberations are often “timid.” When have you felt uncertain or timid when making a big decision? How does the idea of an “indwelling of divine wisdom” change how you might approach future decisions?

- What does it mean to see your life from “God’s perspective”? How might that perspective differ from your own, especially during times of struggle or confusion?

- Describe a time you felt a “quiet, guiding presence” that you believe might have been the Holy Spirit. How can we become more attentive to this daily grace from our Baptism?

BAPTISM

The New Family of God

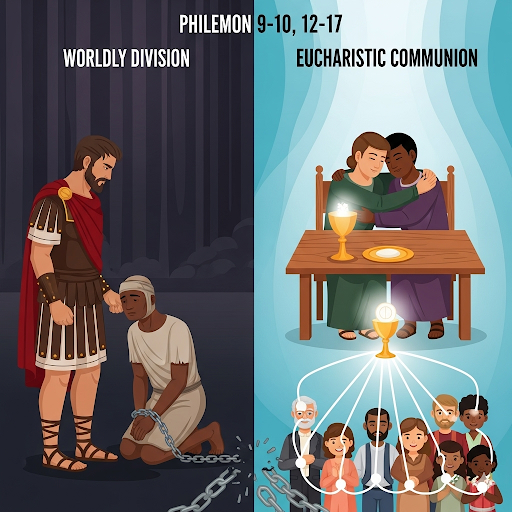

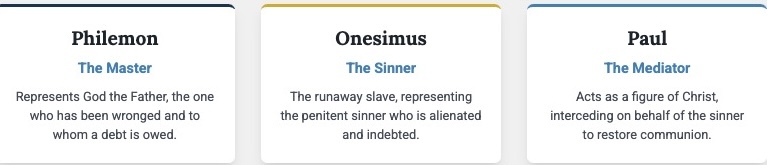

Paul’s plea for Philemon to receive Onesimus “no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a beloved brother” (v. 16) reveals the radical new reality created by Baptism.

This sacrament does more than wash away sin; it bestows a new identity and forges a supernatural kinship. The unique daily grace of Baptism is the power to see every person through the lens of this new reality.

It is the grace that dismantles the worldly walls of status, race, and background that divide us. In our daily interactions at work, in our communities, or even within our own families, this grace challenges us to look beyond external labels. It empowers us to recognize the inherent dignity of each person as a fellow child of God, a “beloved brother” or sister “in the Lord” (v. 16), and to treat them with the love and respect that this new relationship demands.

Second Reading

23rd Sunday of Year C

Reflection Questions

- Paul’s request to Philemon was radical for its time. What are some of the modern “worldly distinctions” or labels (social, political, economic) that create division between people today?

- Baptism gives us a “new, shared identity.” How does remembering this shared identity as “children of God” challenge you to interact differently with people you disagree with or find difficult?

- Think about your daily interactions—at work, in your neighborhood, or online. What is one practical way you could “look beyond labels” this week to better recognize the dignity of another person, as called for by our Baptism?

BAPTISM

The Foundational “Yes”

Jesus’s call to discipleship is absolute: we must be willing to renounce everything and carry our cross (v. 27, 33). The Sacrament of Baptism is our foundational “yes” to this demanding call; it is our enlistment.

In this sacrament, we die to our old selves and rise to a new life oriented completely toward Christ. The unique daily grace of Baptism is the strength for ongoing conversion.

It is the fundamental power to live out that initial renunciation day by day. When faced with the temptation to be selfish, to prioritize comfort over charity, or to follow our own will instead of God’s, we draw upon this grace.

It is the strength to pick up the “cross” of small, daily sacrifices and to continually choose Christ over the “possessions” of our pride and self-interest, making our entire life a journey of discipleship.

Gospel Reading

23rd Sunday of Year C

Reflection Questions

- Jesus uses the analogies of building a tower and waging a war, both of which require careful planning and commitment. Why do you think he emphasizes “calculating the cost” of discipleship? What does this say about the significance of our baptismal promises?

- The essay speaks of renouncing things that “hold us back from God.” What are some common, everyday attachments (e.g., comfort, control, approval of others) that can become obstacles in our relationship with Christ?

- What does it mean for you to “renew this baptismal promise” on a daily basis? What is one small, conscious choice you can make today to place God first and “build your life on His foundation”?ose around us?

EUCHARIST

The Taste of Wisdom

Paul’s plea for Philemon to see Onesimus as a “beloved brother” rather than a slave reveals the heart of Christian community.

The Eucharist is the very source and summit of this new reality. It is more than a symbol of unity; it is the cause of it. When we approach the altar, all worldly distinctions of status, wealth, and background dissolve. In receiving the one Body of Christ, we are supernaturally fused into one Body, the Church.

The daily grace flowing from the Eucharist is a profound strengthening of charity. It empowers us to look past grievances and social labels and see Christ in the person next to us. This sacramental communion challenges us to bring reconciliation to our families, workplaces, and divided communities, transforming our relationships from worldly contracts into bonds of supernatural kinship in the Lord.

First Reading

23rd Sunday of Year C

Reflection Questions

- Faith can lead us down a path that is “illogical to the world.” Can you think of a time when you felt called to act in a way that didn’t make practical sense, but felt right in your heart?

- What does “spiritual clarity” mean to you in your daily life? Is it about having all the answers, or is it more about having a sense of peace and trust in the midst of uncertainty?

- How can you more intentionally bring a specific worry or a difficult decision to prayer after receiving the Eucharist, asking for the grace of divine wisdom?

EUCHARIST

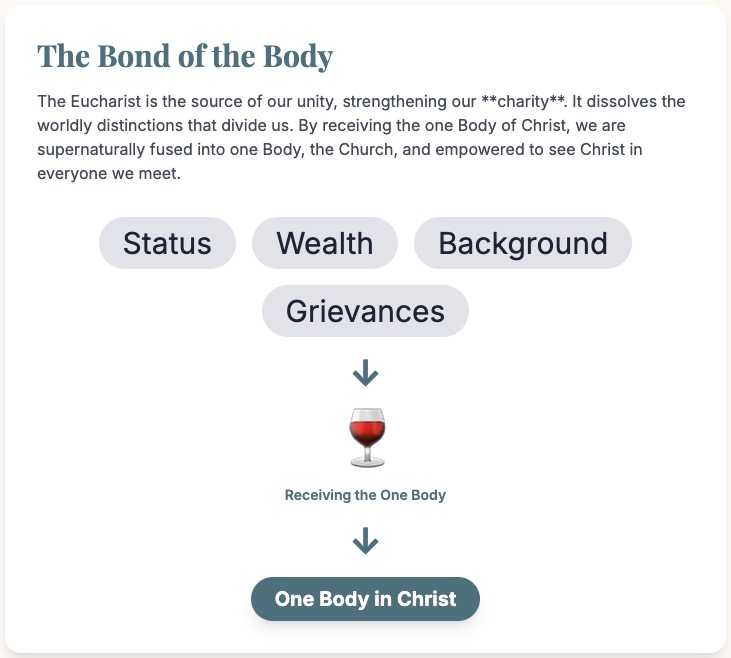

The Bond of the Body

Paul’s plea for Philemon to see Onesimus as a “beloved brother” rather than a slave reveals the heart of Christian community.

The Eucharist is the very source and summit of this new reality. It is more than a symbol of unity; it is the cause of it. When we approach the altar, all worldly distinctions of status, wealth, and background dissolve. In receiving the one Body of Christ, we are supernaturally fused into one Body, the Church.

The daily grace flowing from the Eucharist is a profound strengthening of charity. It empowers us to look past grievances and social labels and see Christ in the person next to us. This sacramental communion challenges us to bring reconciliation to our families, workplaces, and divided communities, transforming our relationships from worldly contracts into bonds of supernatural kinship in the Lord.

Second Reading

23rd Sunday of Year C

Reflection Questions

- In receiving the Eucharist, we are “supernaturally fused into one Body.” How does this truth challenge the way you view the people you sit next to at Mass, especially those you don’t know or may have disagreements with?

- Think of a relationship in your life that is strained or a community that is divided. How can the grace of Eucharistic charity empower you to be a source of reconciliation in that situation?

- What is one “worldly distinction” or label (social, political, etc.) that you find yourself applying to others? What is one practical step you can take this week to consciously “look past” that label?

EUCHARIST

Sustenance for

The Journey

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus makes it clear that the path of discipleship is demanding, requiring us to carry our cross and renounce all that holds us back. He does not, however, ask us to walk this path on our own strength.

The Eucharist is the divine provision for this arduous journey. It is the Bread of Life, the spiritual nourishment that equips us for the cost of following Him.

The daily grace of the Eucharist is supernatural fortitude. When our own resolve weakens and the cross feels too heavy, receiving Christ’s Body and Blood infuses us with His own sacrificial strength and divine life. It is our viaticum, our food for the way, empowering us to persevere in our commitments, to make the small daily sacrifices, and to continue building our lives on His foundation, even when we feel we have nothing left to give.

Gospel Reading

23rd Sunday of Year C

Reflection Questions

- Jesus speaks of the “cost of discipleship.” What is a specific “cross” or ongoing challenge in your life right now where your own strength feels insufficient?

- The Eucharist is “food for the way.” How can you shift your mindset to see receiving Communion not just as a weekend ritual, but as receiving essential spiritual fuel for the week ahead?

- What is one “small daily sacrifice” you are being called to make (e.g., patience, forgiveness, generosity with your time)? How can you unite that sacrifice with the strength you receive from the Eucharist?

CONFIRMATION

Sealed for Sound Judgment

The Book of Wisdom highlights a fundamental human dilemma: our earthly perspectives are limited, and our “deliberations are timid.”

We struggle to discern God’s will. Confirmation is the definitive answer to this struggle, sealing us with the Holy Spirit and perfecting our baptismal grace. It specifically bestows the gift of Counsel, equipping our souls for mature spiritual discernment.

The daily grace of Confirmation is right judgment. It is the inner prompting of the Spirit that brings clarity to our complex moral and vocational questions. When faced with a career change, a difficult ethical choice at work, or a major family decision, this grace moves beyond timid human reasoning. It empowers us to confidently assess the situation not by worldly standards, but with the supernatural prudence of God, allowing us to choose the path that leads to true holiness and peace, aligning our will with the divine plan.

23rd Sunday of Year C

First Reading

Reflection Questions

- Our “deliberations are timid.” Think of a time you faced a major decision (about a career, relationship, or family) and felt uncertain. How might the grace of “right judgment” have brought clarity or confidence to that situation?

- What is the difference between making a decision based on “worldly standards” (like success, comfort, or popular opinion) versus making one with “supernatural prudence”? Can you think of a real-life example?

- How can you more intentionally invite the Holy Spirit’s gift of Counsel into your decision-making process this week?

CONFIRMATION

Commissioned for Witness

In his letter, Paul acts not just as a friend, but as a bold ambassador for Christ, courageously advocating for Onesimus based on the truth of the Gospel. He provides a living example of the mission given to every Christian.

The sacrament of Confirmation bestows the unique grace to live out this mission publicly. It is the anointing that transforms a private believer into a public witness, a spiritual soldier for Christ.

The daily grace of Confirmation is supernatural courage. This is the fortitude that enables us to defend our faith with charity when it is challenged, to speak out against injustice in our communities, or to share our personal testimony when a friend is struggling. It is the strength to stand firm in our convictions when faced with social pressure, making our entire lives a credible witness to the transformative power of Jesus Christ.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Second Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay contrasts a “private believer” with a “public witness.” What do you think is the key difference between the two in terms of daily actions and attitudes?

- Which scenario requires more courage for you personally: defending your faith in a conversation, speaking out against a local injustice, or sharing your personal testimony with a friend? Why?

- What is one small, concrete way you could be a more courageous “ambassador for Christ” in your family, workplace, or community this week?

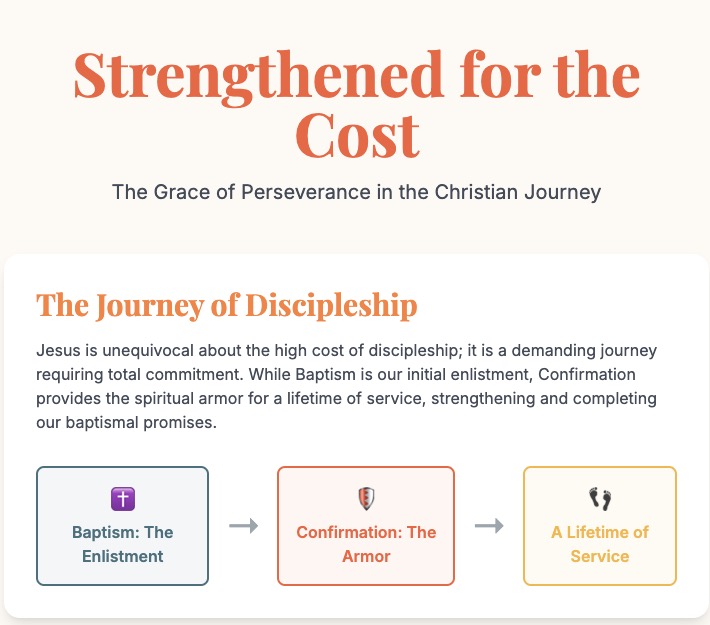

CONFIRMATION

Strengthened for the Cost

Jesus is unequivocal about the high cost of discipleship; it is a demanding journey that requires total commitment.

While Baptism is our initial enlistment, Confirmation is the sacrament that provides the spiritual armor for a lifetime of service. It strengthens and completes our baptismal promises, equipping us to endure the challenges of the Christian life.

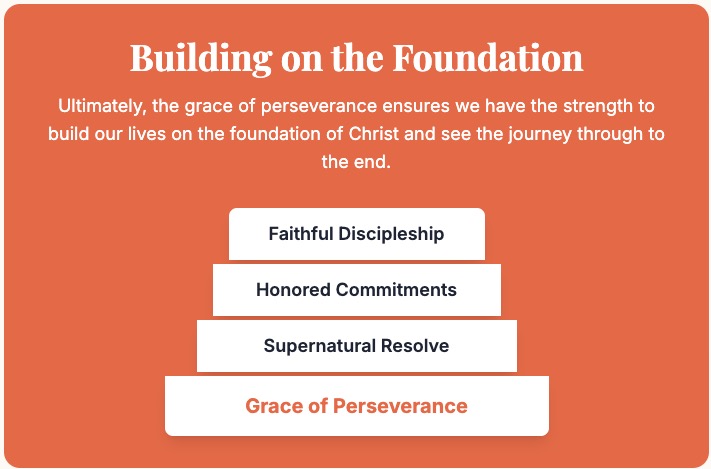

The daily grace of Confirmation is perseverance in faith. When the initial zeal of our conversion fades, when prayer becomes difficult, or when the cross of our daily duties feels heavy, this grace provides the spiritual stamina to remain faithful. It is the supernatural resolve that empowers us to honor our commitments, to resist the temptation to take the easier path, and to continue building our lives on the foundation of Christ, ensuring we have the strength to see the journey through to the end.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Gospel Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay mentions challenges like “fading zeal,” “difficult prayer,” and “heavy daily duties.” Which of these challenges most resonates with your own spiritual journey right now?

- How does viewing Confirmation as providing “spiritual stamina” or “armor” change your perspective on facing the routine difficulties and temptations of your day?

- What specific commitment in your life (a relationship, a vocation, a promise) currently requires the grace of perseverance the most? How can you lean on the strength given in your Confirmation to remain faithful to it?

CONFESSION & PENANCE

Clarity of a Clean Heart

The Book of Wisdom speaks of our “timid deliberations,” highlighting how our earthly nature clouds our judgment. Sin amplifies this confusion, weighing down the soul and making it difficult to discern God’s will.

The Sacrament of Reconciliation is God’s direct remedy for this spiritual blindness. In confessing our sins and receiving absolution, the fog is lifted.

The unique daily grace of this sacrament is a restored clarity of conscience. It is not merely the emotional relief of being forgiven, but the supernatural restoration of our ability to judge rightly. This grace allows us to approach our daily decisions—at work, in our families, and in our moral lives—with renewed confidence. No longer paralyzed by past failures or confused by guilt, we can more easily perceive the promptings of the Holy Spirit and choose the path that aligns with God’s peaceful and loving plan for our lives.

23rd Sunday of Year C

First Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay describes sin as amplifying confusion and “weighing down the soul.” Can you think of a time when a past mistake or a guilty conscience made it difficult for you to make a clear decision?

- What is the difference between the simple “emotional relief” of being forgiven and the “supernatural restoration of our ability to judge rightly”?

- How can you more intentionally bring a specific area of confusion in your life to the Sacrament of Reconciliation, asking God for the grace of a clean heart and a clear mind?

CONFESSION & PENANCE

Mending the Mystical Body

Paul’s plea for Philemon to receive Onesimus back “no longer as a slave but… a beloved brother” is a powerful model for the healing that occurs in Reconciliation.

Every sin we commit has a dual effect: it damages our personal relationship with God and it wounds the Mystical Body of Christ, the Church. The grace of this sacrament is therefore twofold, offering both divine pardon and ecclesial repair.

The unique daily grace of Reconciliation is the power of communal healing. By humbly admitting our faults, we are strengthened to both seek and grant forgiveness in our human relationships. This grace empowers us to mend the bonds broken by our impatience, gossip, or anger. It challenges us to stop keeping a record of wrongs and to see others as God sees them: beloved, fallen, and always worthy of a chance at reconciliation.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Second Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay states that every sin “wounds the Mystical Body of Christ.” How does this perspective change your understanding of so-called “private” sins?

- Think of a relationship in your life that has been damaged by impatience, gossip, or anger. How does the grace of this sacrament strengthen you to be a source of healing in that situation?

- What does it mean to “stop keeping a record of wrongs” and see others as God sees them: “beloved, fallen, and always worthy of a chance at reconciliation”?

CONFESSION & PENANCE

The Renunciation of Fault

In the Gospel, Jesus speaks of the necessity of renouncing all our “possessions” to be his disciple. Our sins, especially habitual ones, are the most toxic possessions to which we cling.

The Sacrament of Reconciliation is the practical and powerful means by which we renounce them. The penance we receive is not a punishment, but a form of spiritual therapy designed to help us detach from our specific faults.

The unique daily grace of this sacrament is the strength for ordered affections. It helps us to love God above all else and to reorder our desires away from sin. If we confess selfishness, an act of charity helps detach us from self-love. If we confess impurity, prayers for purity reorient our hearts. This grace strengthens our resolve, empowering us to live in the freedom of God’s children, unburdened by our attachments.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Gospel Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay calls our sins our “most toxic possessions.” Which habitual fault or attachment do you find yourself clinging to most tightly?

- How does viewing penance as “spiritual therapy” rather than a punishment change your attitude toward performing it?

- The essay mentions that an act of charity can help detach from selfishness. What is one concrete action you could take this week as a form of “penance” to help reorder your desires and strengthen your resolve against a specific, recurring temptation?

ANOINTING OF THE SICK

The Wisdom of Surrender

The Book of Wisdom reminds us that God’s ways are beyond our understanding, a truth never more potent than in the face of suffering. Illness can cloud our minds with fear and doubt, making our deliberations “timid.”

The Anointing of the Sick is God’s direct response to this spiritual confusion. It bestows the unique grace of peaceful acceptance, strengthening the soul against the temptation to despair or grow angry with God.

The daily grace for one suffering a prolonged illness is the supernatural ability to surrender to God’s will with profound trust. This sacrament does not promise a physical cure, but offers a deeper healing. It helps us to actively unite our pain, weakness, and anxiety to the Cross of Christ, transforming what feels meaningless into a redemptive offering. Through this grace, we can find a supernatural purpose in our suffering, even when physical healing is not granted.

23rd Sunday of Year C

First Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay mentions that illness can make our deliberations “timid.” In your experience, how does suffering or serious illness affect a person’s ability to think clearly and trust in God?

- What is the difference between “giving up” in despair and the “peaceful acceptance” or “surrender” that this sacrament offers?

- How can we, as a community, support those who are ill in finding a “redemptive purpose” in their suffering, rather than just offering prayers for a physical cure?

ANOINTING OF THE SICK

Anointed into Communion

Paul’s plea for Philemon to welcome Onesimus highlights the radical communion of the Christian family. Serious illness, however, can lead to a profound sense of isolation, making the sick feel forgotten, burdensome, and cut off from the Body of Christ.

The Anointing of the Sick powerfully counteracts this spiritual separation. Its unique grace is the strengthening of our bond with the Church. When a priest, representing Christ and the community, anoints a sick person, it is a tangible sign that the entire Mystical Body is praying for and suffering with them.

This grace reminds the homebound or hospitalized that they are never alone. It reaffirms their place as a vital, cherished, and prayerful member of God’s family, whose sufferings have value for the whole Church. This anointing breaks through the walls of isolation and restores a deep sense of belonging.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Second Reading

Reflection Questions

- Why is the feeling of isolation often one of the most difficult parts of a serious illness? Have you ever witnessed or experienced this?

- The essay states the priest represents “Christ and the community.” How does this understanding change your perspective on the role of the priest and the sacrament itself?

- What are some practical ways a parish community can live out this grace and ensure its sick and homebound members feel like “vital, cherished, and prayerful members” of the family?

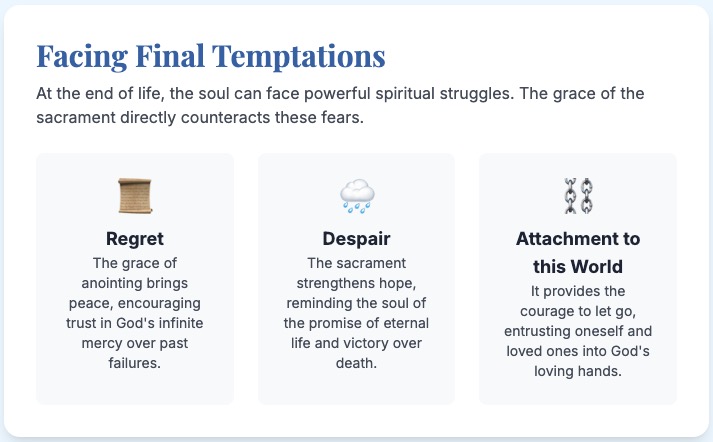

ANOINTING OF THE SICK

Strength for the Final Cost

Jesus speaks of the great cost of discipleship, a journey that culminates in our final passage from this life to the next. This ultimate journey requires immense spiritual strength.

The Anointing of the Sick is God’s specific provision for this final battle, which is why it is often called the “sacrament of the dying.”

It provides the grace of fortitude for a holy death, arming the soul for its last and most important test. This anointing strengthens the soul against the final temptations of fear, regret, and despair, which can be especially powerful in our final moments. It gives the dying person the courage to renounce their attachment to this world and to entrust themselves completely and without reservation into God’s loving mercy, preparing them for a peaceful and confident passage into eternal life with Him.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Gospel Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay describes this anointing as “spiritual armor for a final battle.” What are some of the fears or temptations (like regret, despair, or attachment to this world) that a person might face at the end of their life?

- How does the grace of “fortitude for a holy death” differ from simple human bravery or acceptance of the inevitable?

- This sacrament is not only for the moment of death. How can receiving the Anointing of the Sick during a serious illness help prepare a person for their “final passage,” whenever it may come?

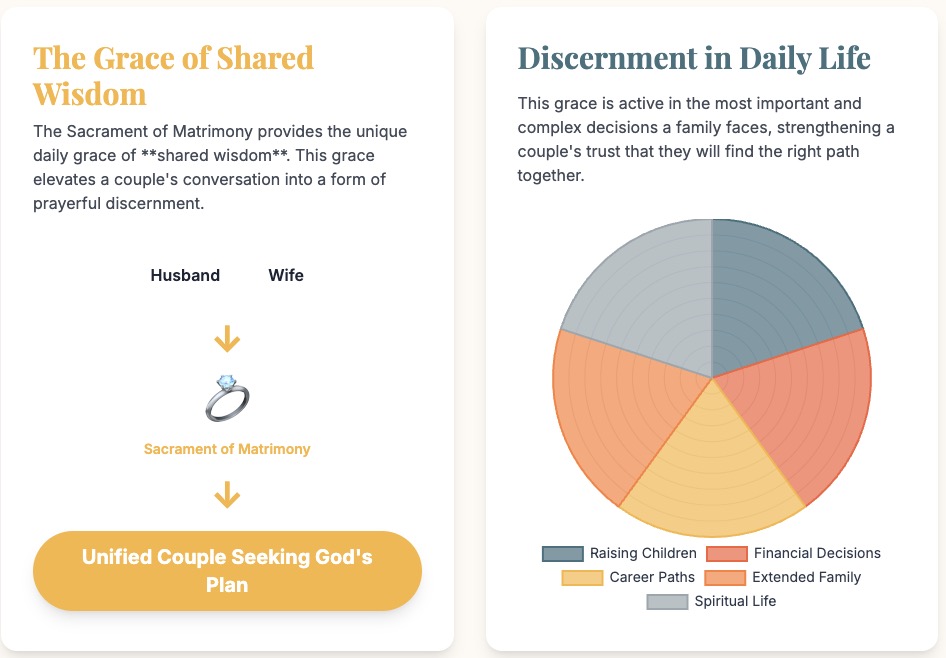

MATRIMONY

A Shared Path Made Straight

The Book of Wisdom asks, “who can discern what the LORD wills?” (v. 13), a question that resonates deeply within the vocation of marriage. Two individuals, with their own “timid deliberations,” must become one in discerning a shared path.

The Sacrament of Matrimony provides the unique grace for this lifelong task: shared wisdom. This is the daily grace that allows a husband and wife to see beyond their individual perspectives and approach life’s complex decisions as a unified couple seeking God’s plan.

When facing choices about careers, finances, or raising children, this sacramental grace elevates their conversation into a form of prayerful discernment. It strengthens them to trust that, by seeking God’s will together, their “paths…on earth [are] made straight” (v. 18b). Their union becomes a testament that two people, united in Christ, can indeed learn the counsel of God for their family.

23rd Sunday of Year C

First Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay mentions that couples must become “one in discerning a shared path.” What are some of the biggest challenges couples face when trying to make major life decisions together (e.g., finances, careers, parenting)?

- What is the difference between a couple simply compromising and a couple engaging in “prayerful discernment”? How does the grace of the sacrament elevate this process?

- Can you think of a time when you and your spouse (or another couple you know) felt that a decision you made together brought you a sense of peace and rightness, as if your path was “made straight”?

MATRIMONY

More Than a Contract

Paul’s plea for Philemon to receive Onesimus “no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a beloved brother” (v. 16) mirrors the radical transformation that occurs in Matrimony.

A marriage is not a worldly contract based on feelings or benefits; it is an indissoluble covenant that creates a new reality of kinship. The unique daily grace of this sacrament is persevering, covenantal love. This is the supernatural strength that empowers a husband and wife to continue seeing each other as a “beloved” gift, especially during times of trial, disagreement, or the mundanity of daily life.

When frustrations arise, this grace calls them to look beyond the immediate fault and see the person to whom they are permanently bound in Christ. It is the power to forgive daily, to choose charity over resentment, and to live out their vows “for better, for worse.”

23rd Sunday of Year C

Second Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay contrasts a “worldly contract based on feelings or benefits” with an “indissoluble covenant.” What are some ways modern culture treats marriage more like a contract?

- How does the grace of “covenantal love” help a couple navigate the “mundanity of daily life” or periods when feelings of romance might fade?

- Paul asks Philemon to look beyond Onesimus’s past fault. What does it practically mean for a spouse to “look beyond the immediate fault” and see the person to whom they are permanently bound in Christ?

MATRIMONY

The Fruitful Cross of the Family

Jesus makes it clear that discipleship requires renouncing all our possessions and carrying our cross (v. 27, 33).

For most, the Sacrament of Matrimony is the primary school for this lesson in self-denial. The vocation is a constant call to renounce one’s own will, schedule, and desires for the good of the spouse and children.

The unique daily grace of Matrimony is generous self-gift. This grace transforms what could be burdensome duties into acts of sacrificial love. It is the strength that allows a parent to joyfully wake up for a sick child, a husband to patiently listen after a long day, or a wife to support her husband’s needs above her own. This grace makes it possible to “carry his own cross” (v. 27) not with bitterness, but with a generous heart, making the family a place where love is perfected through daily sacrifice.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Gospel Reading

Reflection Questions

- The essay calls marriage a “constant call to renounce one’s own will, schedule, and desires.” In what specific, everyday ways have you found this to be true in your own family life or in observing others?

- What is the difference between carrying the “cross” of family duties with bitterness versus carrying it with a “generous heart”? How does the grace of the sacrament make the latter possible?

- Describe a time when you witnessed or experienced a simple act of service within a family (like a parent caring for a sick child) that was clearly an act of “sacrificial love.”

HOLY ORDERS

The Counsel of the Shepherd

The Book of Wisdom asks, “who ever knew your counsel, except you had given wisdom and sent your holy spirit from on high?” (v. 17). This question highlights the immense responsibility of a priest or deacon, who must guide souls along a path he himself cannot fully see.

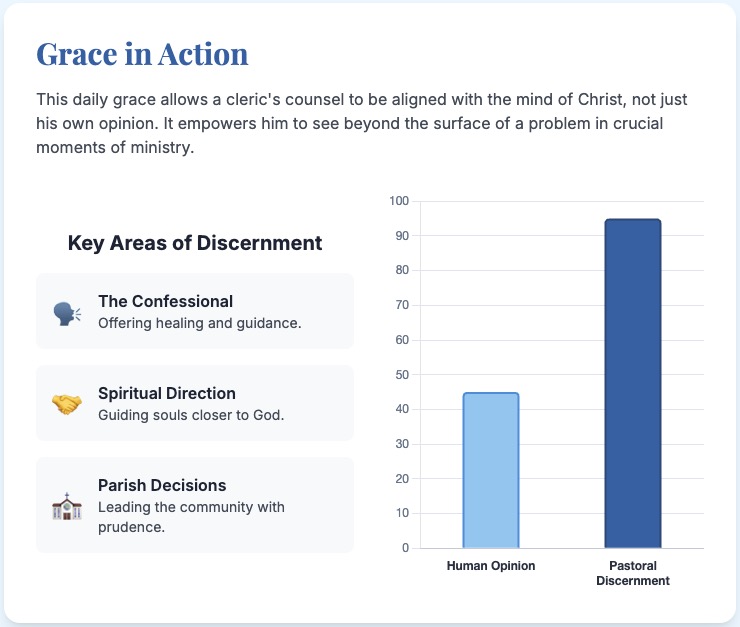

The Sacrament of Holy Orders bestows a unique grace for this task: pastoral discernment. This is a special gift of the Holy Spirit, perfecting the virtue of prudence for the sake of the Church.

The daily grace for a cleric is the ability to offer counsel that is not merely his own opinion, but is aligned with the mind of Christ. In the confessional, during spiritual direction, or when making decisions for the parish, this grace allows him to see beyond the surface of a problem and guide the faithful with the supernatural wisdom needed to make their “paths…on earth straight” (v. 18b).

23rd Sunday of Year C

First Reading

Reflection Questions

- A priest must “guide souls along a path he himself cannot fully see.” Why is this such an immense and humbling responsibility?

- What are the potential dangers when a spiritual leader relies only on their own human wisdom or personal opinions to guide others?

- There is a distinction between a cleric’s “own opinion” and counsel that is “aligned with the mind of Christ.”What do you think is the key difference between these two things?

- How does the idea that this is a “special gift of the Holy Spirit” change your perspective on the advice you might receive from a priest or deacon?

- The grace is described as perfecting prudence “for the sake of the Church.” How is this different from the prudence any person tries to practice in their own life?

- The graphic above shows three specific areas where this grace is applied: the confessional, spiritual direction, and parish decisions. Why is the ability to “see beyond the surface of a problem” particularly important in each of these three areas?

- Have you ever received advice or guidance from a priest that you felt was more than just good human advice—something that truly helped you see your situation with new clarity? What made it different?

- The ultimate goal of this grace is to help make the faithful’s “paths…on earth straight.” What does a “straight path” toward holiness look like in the midst of a complicated and “winding” modern life?

- How does receiving wise, Spirit-led counsel from a shepherd help us stay on that path?

HOLY ORDERS

A Father’s Heart

When Paul speaks of Onesimus, he does so as a spiritual father, “sending him, that is, my own heart, back to you” (v. 12). This reveals the essence of the priesthood.

Through Holy Orders, a man is configured to Christ the Head, and the unique grace he receives is spiritual paternity. This is not simply a role he plays, but a new identity.

The daily grace for a priest is the supernatural love that allows him to see his parishioners as his own children. It is the joy he feels at a baptism, the sorrow he shares at a funeral, and the patient love he offers in the confessional. This grace empowers him to pour out his life, to send his “own heart” to his people day after day, nourishing, guiding, and protecting the family of God entrusted to his care.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Second Reading

Reflection Questions

- Spiritual paternity is a “new identity,” not just a role a priest or deacon plays. What is the difference between having a role and having a new identity?

- St. Paul tells Philemon he is sending his “own heart” back with Onesimus. What does this powerful phrase tell you about the depth of love a spiritual father has for his children?

- Specific examples of a priest’s fatherly love: joy at baptisms, sorrow at funerals, and patience in confession. Which of these examples most powerfully illustrates the idea of spiritual fatherhood to you, and why?

- Have you ever witnessed a priest or deacon acting with a love or patience that seemed to go beyond ordinary human emotion? How did it impact you?

- What does it mean for a priest or deacon to “pour out his life” for his people day after day? What are some of the hidden, daily sacrifices this might involve?

- A priest and deacon’s duties invovle nourishing, guiding, and protecting. How can parishioners best support their priests and deacons in fulfilling these demanding aspects of their fatherly care?

HOLY ORDERS

The Living Sacrifice

Jesus demands a radical renunciation from his disciples: “every one of you who does not renounce all his possessions cannot be my disciple” (v. 33). While all Christians are called to this, the priest lives it in a unique and total way through his vows of celibacy and obedience.

The Sacrament of Holy Orders imparts the grace of configuration to Christ the Servant, who offered himself completely on the Cross.

The daily grace of this sacrament is the strength for sacrificial service. It is the supernatural fortitude that enables a priest to offer his time, his personal desires, and his very life for his flock. This grace is lived out when he wakes in the night for a hospital call, spends hours in the confessional, or offers his lonely moments for the salvation of souls, making his entire existence a living sacrifice united to the Eucharist he celebrates.

23rd Sunday of Year C

Gospel Reading

Reflection Questions

- A priest lives out the call to “renounce all his possessions” in a “unique and total way.” How do the vows of celibacy and obedience represent a total renunciation?

- While not all are called to be priests, all Christians are called to this renunciation. What “possessions” (material, emotional, or otherwise) do you find most difficult to renounce in your own life to follow Christ more closely?

- What does it mean to be “configured to Christ the Servant”? How is this different from simply trying to imitate Christ’s actions?

- The grace for sacrificial service is a “supernatural fortitude.” Why is it important to recognize this strength as supernatural rather than just a priest’s own personal willpower or kindness?

- Three examples of a priest’s sacrificial service are: a hospital call, hours in the confessional, and offering lonely moments. Which of these examples gives you the deepest insight into the daily reality of a priest’s life? Why?

- How can we, as parishioners, be more mindful and supportive of the hidden, daily sacrifices our priests make for the salvation of souls?

INTRODUCTION: The sacraments are important for Catholics to grow in their relationship with God. They are not just one-time events but ongoing experiences. THE WORD THIS WEEK connects each sacrament to the Sunday readings in its LIVING THE WORD section. You can also find a DEEP DIVE into one sacrament to learn more. Priests and deacons might find this useful when preparing their homilies. If the essay doesn’t connect with you right now, feel free to explore the reflection questions and infographics on the other pages of this section.

RECONCILIATION

Divine Wisdom, Radical Discipleship, and Ecclesial Restoration in the Sacrament of Penance

Wisdom 9:13-18b

Philemon 9-10, 12-17

Luke 14:25-33

The Shattered Counsel of Man and the Reconciling Wisdom of God

The Book of Wisdom asks a key question that shapes our understanding of humanity: “Who can know God’s counsel, or who can conceive what the LORD intends?” It paints a challenging picture of human nature, saying our thoughts are timid and plans uncertain because our physical bodies burden our souls. The text says we can’t even fully understand things on Earth, let alone God’s will.1 This biblical view matches the Church’s teaching on Original Sin, explaining why humans have a hard time knowing and doing what is right.

Modern Church teachings agree with this ancient view. Pope John Paul II said our world is broken by conflicts rooted in sin, which is like a wound in each person.5 Both he and Pope Pius XII worried that people today have lost the sense of sin.7 Pope Benedict XVI added that, strangely, while people feel less guilty for sins, they feel more guilty in general.8 When people try to live without God, they may end up feeling empty and anxious.8

So, what’s the solution? According to Wisdom, it’s God’s wisdom and the Holy Spirit.1 The Catholic Church teaches that the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation is how we get this help.10 After Baptism, it’s the way to get forgiveness for our sins.11 Reconciliation is how God answers our need for help and helps us fix our mistakes, grow closer to Him, and become wiser.

Part I: The Divine Initiative

Reconciliation is a gift from God, not a human accomplishment. It starts with God’s mercy, given to us through Jesus and His Church. The way the sacrament works shows us that sin affects everyone, so fixing it means fixing our relationships with each other and the community, not just ourselves.

The Christological Pattern of Mediation in Philemon

In his letter to Philemon, St. Paul sets a powerful example of Christ-like mediation by interceding for the runaway slave Onesimus. Although Paul has the authority to order Philemon to do what is right, he chooses instead to appeal out of love and vulnerability.13 He identifies deeply with Onesimus, calling him “my child” and even “my own heart.”1

The pinnacle of Paul’s mediation comes when he takes upon himself the debt and responsibility of Onesimus, declaring, “And if he has done you any injustice or owes you anything, charge it to me. I, Paul, write this in my own hand: I will pay.”15 In this selfless act, Paul embodies the redemptive love that Christ demonstrated on the Cross, bearing the guilt and liability of sinners to bring about reconciliation and healing. Through this profound example, we are shown the power of love and voluntary sacrifice in restoring broken relationships.

This Pauline model is sacramentally embodied in the ministry of the priest in the confessional. The Catechism teaches that Christ, after His resurrection, entrusted the “exercise of the power of absolution to the apostolic ministry”.10 Priests, as successors to the apostles, are instruments who forgive sins “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”.17 The priest is the “sign and the instrument of God’s merciful love for the sinner”.9

Pope Benedict XVI clarifies the ontological reality of this ministry, stating that penitents approach the confessor “only because we are priests, configured to Christ the Eternal High Priest, and enabled to act in his Name and in his Person, to make God who forgives, renews and transforms, truly present”.18 Thus, just as Paul stood in the breach for Onesimus, the priest in the confessional stands in persona Christi Capitis. The words of absolution are not his own; they are the performative utterance of Christ Himself, who through His minister sacramentally assumes the penitent’s debt and communicates the Father’s infinite mercy.

The Ecclesial Dimension of Forgiveness

The goal of Paul’s mediation for Onesimus was not merely a private pardon but a public, ecclesial restoration. Onesimus, as a runaway slave and possible thief, was alienated not only from his master but from the entire household community.15 His sin had a concrete social and ecclesial dimension. Consequently, Paul’s desired outcome is a radical transformation of Onesimus’s status within that community. Philemon is instructed to receive him “no longer as a slave, but more than a slave, a beloved brother… both as a man and in the Lord”.1 He is to be welcomed with the same honor as the Apostle himself.1 This demonstrates that for Paul, authentic reconciliation is revolutionary; it does not simply restore the status quo but elevates the sinner into a new, grace-filled mode of communion.

This scriptural paradigm reveals the Church’s dogma on the twofold effect of absolution. The Catechism states unequivocally: “

Sin is before all else an offense against God, a rupture of communion with him. At the same time it damages communion with the Church.

Thus, Pope Benedict XVI powerfully articulates the reality that sin is never just a “personal” matter between an individual and God. “Sin always has a social dimension, a horizontal one,” he explains. “I have damaged the communion of the Church”.21

This wound to the Body of Christ requires that absolution occur “at the level of the human community,” to “fully reintegrate” the sinner.21 The ancient practice of public penance for grave sins, described by theologians like St. Augustine, historically underscores this communal reality, where sinners were formally separated from and then readmitted to the ecclesial body.22

The very structure of Paul’s intervention—insisting that Onesimus physically return to the community he wronged—is a potent corrective to a purely abstract or “spiritualized” notion of forgiveness. A utilitarian approach might have led Paul to keep the now “useful” Onesimus with him, declaring him forgiven in spirit.13 Instead, Paul undertakes the costly and risky act of sending him back, because the reconciliation is incomplete until it is lived out in the concrete, embodied reality of the house-church.1 This parallels the sacrament’s own structure. Forgiveness is not a silent, mental transaction. It requires the concrete acts of going to a priest, speaking sins aloud, and receiving a tangible penance, grounding the reality of forgiveness in the visible life of the Church.

Part II: The Human Response

While reconciliation is a divine initiative, it demands a free and total human response. The acts of the penitent in the sacrament are the concrete means by which an individual embraces the radical, all-encompassing demands of discipleship articulated by Christ in the Gospel of Luke.

The Sober Calculation of the Penitent

In Luke 14, Jesus presents two parables to the great crowds following him: one of a man intending to build a tower, and another of a king preparing for battle. In both scenarios, the protagonist’s first action is to “sit down and calculate the cost” or “sit down and decide”.1 A failure to make this sober assessment leads to public humiliation or military catastrophe, demonstrating that the stakes are absolute.1 These parables are not lessons in worldly prudence but solemn warnings about the gravity of Christian discipleship. As one biblical commentator observes, “Following Jesus is an all or nothing proposition”.26

This Lukan imagery of “sitting down to calculate the cost” serves as a perfect scriptural model for the penitent’s preparation for confession. The Catechism teaches that the essential acts of the penitent begin with a “careful examination of conscience,” which is the necessary prelude to authentic contrition.11 This examination is not a cursory review of faults but a “radical reorientation of our whole life, a return, a conversion to God with all our heart”.16 It culminates in a “firm purpose of sinning no more in the future”.11 In the examination of conscience, the penitent sits down, as it were, to calculate the devastating “cost” of sin—alienation from God and His Church—and the demanding “cost” of returning—a complete reordering of one’s life. In this moment of profound honesty, the penitent deliberately chooses the path of conversion, recognizing it as the only one that does not end in spiritual ruin.

Renunciation and the Acts of the Penitent

The cost of discipleship, as calculated by Christ, is total renunciation. He issues the challenging demand: “If anyone comes to me without hating his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple”.1 Biblical scholarship recognizes this as a form of Semitic hyperbole, the meaning of which is clarified in the parallel passage from Matthew: “Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me”.26 The term “hate” signifies a radical detachment and a decisive re-ordering of all loves, enthroning the love of Christ as supreme and absolute. This total renunciation is lived out liturgically through the threefold act of the penitent: contrition, confession, and satisfaction.11

Contrition, especially perfect contrition which “arises from a love by which God is loved above all else,” is the very enactment of this Lukan “hatred.” It is sorrow for sin precisely because it offends God, whom the penitent now chooses above all other attachments, especially the disordered love of self that is the root of all sin. Confession, the disclosure of one’s sins to the priest, is a profound renunciation of pride. It is a concrete act of humility that surrenders the ego’s desire to hide its faults and maintain a false image of righteousness. Finally, satisfaction, the “penance” assigned by the confessor, is meant to “repair the harm caused by sin and to re-establish habits befitting a disciple of Christ”.11 This corresponds directly to Christ’s other non-negotiable demand in the passage: “Whoever does not carry his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple”.1 The act of satisfaction is the willing acceptance of a small cross, a renunciation of spiritual ease, in order to begin repairing the damage of sin.

The consistent use of economic and military language across these texts—”calculate the cost” and “oppose another king” in Luke, and “charge it to me” and “I will pay” in Philemon—reveals a coherent biblical theology of reconciliation.1 In the examination of conscience, the penitent calculates the cost and realizes they are spiritually bankrupt, unable to pay the debt of sin or win the spiritual war alone. In the confessional, they meet the Mediator who has already paid the infinite price on the Cross. The act of satisfaction, then, is not a repayment of this debt but the small “cross” the penitent accepts as a sign of allegiance to the King who has already won the war and secured the terms of peace.

Part III: The Fruits of Reconciliation: From Alienation to Communion

The convergence of the divine initiative and the human response in the Sacrament of Penance yields transformative fruits, healing the sinner’s relationship with God and restoring them to their rightful place within the ecclesial community.

The Recovery of Grace and the “Straightened Path”

The ultimate promise of the Book of Wisdom, contingent upon God sending His spirit, is that “the paths of those on earth were made straight, and people learned what pleases you, and were saved by wisdom”.1 The Sacrament of Penance is the normative means by which this promise is fulfilled in the life of the baptized Christian. The Catechism enumerates the primary spiritual effects of the sacrament: “reconciliation with God by which the penitent recovers grace,” the “remission of the eternal punishment incurred by mortal sins,” the gift of “peace and serenity of conscience, and spiritual consolation,” and an “increase of spiritual strength for the Christian battle”.11

The recovery of sanctifying grace is the “wisdom” and “holy spirit” being sent anew into the soul of the penitent. This infusion of divine life “straightens the path” by healing the wounded will and re-ordering disordered desires. It “teaches what pleases God” by illuminating the conscience with divine truth. It provides the “increase of spiritual strength” necessary to walk the arduous path of discipleship and to carry the cross. As Pope Benedict XVI teaches, the sacrament provides the “indispensable interior energy to overcome the evil and sin” that marks the Christian pilgrimage.9

The New Creation: A Communion of Brothers

The final fruit of the sacrament is the restoration of the sinner’s ecclesial dignity, a reality perfectly captured in the paradigm of Philemon. The final state of Onesimus is a complete re-creation of his identity. He is no longer defined by his past crime (“runaway”) or his social status (“slave”) but by his new, truer reality in Christ: a “beloved brother”.1 This is not merely a return to the community but an elevation to a higher form of communion.

This is precisely what occurs in the sacrament. Penance “reintegrates forgiven sinners into the community of the People of God from which sin had alienated or even excluded them”.10 It is, in the words of Pope Benedict XVI, a “full readmission to the community of the Church”.21 The Sacrament of Reconciliation is the sacred space where the Church continuously lives out the drama of Philemon. In the confessional, every penitent is an Onesimus—alienated and in debt because of sin. Through the mediation of the priest acting in the person of Christ, the new Paul, the penitent is restored to the community, no longer defined by their sin but re-clothed in their true dignity as a “beloved brother” or sister, a “living stone” in the Church.11 This restoration to the family of God is the ultimate “straightening” of the path.

Conclusion: The Uninterrupted Task of Conversion

The theological arc traced through the Wisdom of Solomon, the Gospel of Luke, and the Epistle to Philemon finds its sacramental apex in the Rite of Penance. From the anthropological recognition of humanity’s need for grace, to Christ’s radical call for a calculated and total conversion, to the Christological and ecclesial pattern of mediated restoration, the sacrament emerges as God’s ordained means for healing the wounds of post-baptismal sin. It is the place where divine wisdom meets human repentance, where the debt of sin is cancelled by the Mediator, and where the crooked path of alienation is made straight by a grace that restores the sinner to full communion with the Triune God and His Church.

This process, however, is not a singular event but an ongoing journey. The Catechism reminds the faithful that “Christ’s call to conversion continues to resound in the lives of Christians. This second conversion is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church”.16 This ongoing conversion is nourished by the frequent reception of the sacrament and lived out in daily acts of reconciliation, prayer, and charity.16 The Sacrament of Penance, therefore, stands as the great and merciful gift by which the faithful, throughout their earthly pilgrimage, can continually “calculate the cost,” renounce their attachments to sin, and through the Church’s mediation, have their paths made straight, being ever more deeply incorporated into the life of the Trinity as beloved children of the Father and brothers and sisters in the Lord.

Sources

- https://bible.usccb.org/bible/readings/090725.cfm

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Wisdom%209%3A13-18&version=NABRE

- https://www.biblestudytools.com/nrsa/wisdom/passage/?q=wisdom+9:13-18

- http://bible.oremus.org/?ql=56366275

- https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_02121984_reconciliatio-et-paenitentia.html

- https://www.piercedhearts.org/jpii/apostolic_exhortations/reconciliatio_paenitentia1.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconciliatio_et_paenitentia

- https://www.archbalt.org/confession-helps-those-with-guilt-complexes/?print=print

- https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/to-participants-in-a-vatican-course-on-the-sacrament-of-penance-6813

- https://www.vatican.va/content/catechism/en/part_two/section_two/chapter_two/article_4/vi…

- https://catholicdos.org/reconciliation

- https://www.phxsta.org/sacraments-reconciliation

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Philemon%209-10%2CPhilemon%2012-17&version=NIV

- http://bible.oremus.org/?ql=56366310

- https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0839/_P11E.HTM

- https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/resource/55062/the-sacrament-of-penance-and-reconciliation-catechism-of-the-catholic-church

- https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/catechism/index.cfm?recnum=4717

- https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2011/march/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20110325_penitenzieria.html

- https://bible.usccb.org/bible/philemon/0

- https://www.blessedtrinitycatholic.org/reconciliation

- https://bigccatholics.blogspot.com/2016/03/pope-benedict-xvi-explains-why-you.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacrament_of_Penance

- https://www.marquette.edu/library/theses/already_uploaded_to_IR/hubba_b_1967.pdf

- https://www.biblestudytools.com/luke/passage/?q=luke+14:25-33

- http://bible.oremus.org/?passage=Luke+14:25-33

- https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-23-3/commentary-on-luke-1425-33

- https://www.bible.com/bible/compare/LUK.14.25-33

- https://catholicproductions.com/blogs/mass-readings-explained-year-c/the-twenty-third-sunday-of-ordinary-time-year-c

- https://www.staugustinessf.org/penance

Text and Infographics on this page were created by THE WORD THIS WEEK using AI generative tools (i.e. Chart.js and Tailwind CSS). They may be copied for personal use or for any non-profit ministry.